In the middle of the quarantine, I received a brick in the mail. A brick I’d searched for a long time, ever since I learned of its existence. A brick connected to my hero: Mr. Rogers.

More on that in a bit.

I’m not only a masonry enthusiast and photographer; I’m also a brick collector, more specifically I’m member #1709 of the International Brick Collectors Association. The association was founded in the 1980s by a group of folks who went hunting in long-abandoned brickyards or demolition sites looking for bricks. Bricks are a tangible piece of history. It’s one thing to have a picture of a historic building place. It’s another to have a five-pound chunk of history.

Some members have upwards of 4,000 bricks and have purpose-built sheds to hold and their literal tons of bricks. I live in an apartment in Chicago and have had to move my collection of five-pound pieces of history three times in the last few years. So for that reason, my collection is understandably meager, coming in at 25 (I think. They’re scattered around the place and sometimes difficult to count).

For me, each brick is special not only because of the brick’s history but because of its place in the history of masonry design. I’d like to share a few with you.

First up, a crisp red brick from St. Louis. This brick joined my collection in 2019 when my friend Jay, a retired art teacher, brought it up to me from St. Louis. I’d met Jay in 2018 when I visited St. Louis and he offered to show me around.

I don’t have an exact date for this brick, but I can guess it was likely produced at the end of the 19th century. St. Louis was blessed with uniform and fine clays that could produce crisp and smooth red bricks. Brickmakers in St. Louis were also pioneers in using pug mills and hydraulic pressure to create very fine bricks.

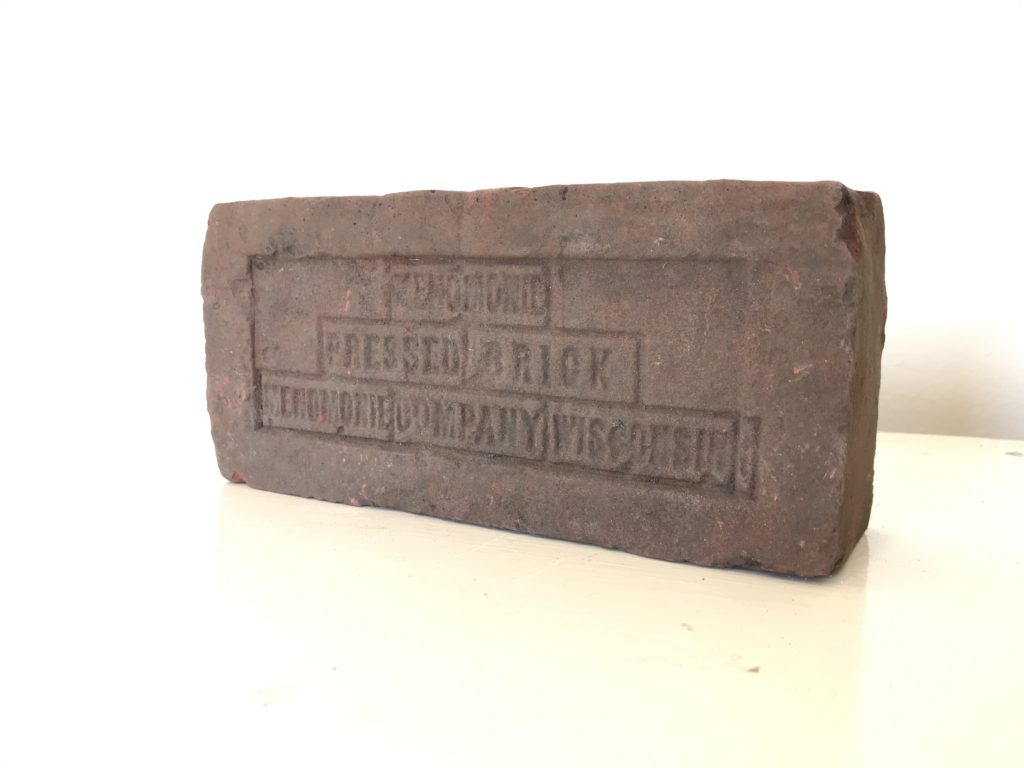

The brick in my collection is a fine example of one of these hydraulically pressed bricks. St. Louis wasn’t the only city to make pressed bricks during this time of smooth red bricks, however. I have two others in my collections, a Menomonie Pressed Brick (from Menomonie, WI) and an Oxford (made by Alwine Brick Co of New Oxford, PA). Pressed bricks are especially valuable to collectors because their stamps make each brand unique.

These smooth red bricks were highly sought after, as fashions of the time called for uniform bricks laid in incredibly tight mortar joints. You can find them in buildings all around Chicago and the country.

This red-brick style didn’t last forever, though. By the early 1900s bricks were becoming more textured and varied in color. I recently added an important piece of that history to my collection in the form of a “Tapestry” Brick, produced by Fiske & Co. based in Boston.

Tapestry brick, used as a generic term, described rough-faced bricks used for front facades. These might have vertical scratches, rug textures, or wire cut faces. While the term was used generically, Fiske actually had a trademark on the name “Tapestry”, going so far to stamp TRADEMARK and REG PAT OFF on the face of their bricks.

As strange as it might seem today, these rough-faced bricks were considered a radical and intentional departure from the smooth bricks of the previous decade.

Why the departure? I’ll let Fiske & Co. explain, with an excerpt from their 1913 Catalogue “Tapestry Brickwork”:

All that need be said about the brick architecture of the early Victorian period, from an artistic standpoint, is that it was the antithesis of everything good. The brickmaker’s ideal seems to have been a single shape and size, a surface like cut cheese, and a color like a fire-cracker…

“Nature has no smooth and polished surfaces. If we build, then, to conform to Nature’s standards, we must discard artificially smooth surfaces, leaving them to those who prefer artificiality to truth.

[Tapestry Brick] is to ordinary brick what Arts and Crafts furniture is to the gilt and velvet of the last century.”

How’s that for marketing?

These two bricks help me feel connected to history and to the buildings I pass every day. But in the middle of quarantine, I found a brick that unexpectedly connected me to my long-time hero, Mr. Rogers.

As an educator and former child, I’ve been immersed in Mr. Rogers’ work for decades. What I didn’t know until recently was that Fred McFeely Rogers’ grandparents, the McFeely’s, made their fortune making McFeely firebricks. Mr. Rogers’ father ran the McFeely Brick Company when Fred was a boy.

Mr. Rogers and bricks? I had to get my hands on one. I looked up the location of the old plant, calculated possible ways to get there, but with quarantine in full effect, I felt I’d never be able to find one.

Until suddenly a post I’d made in the brick collectors’ Facebook group early in my search got a hit. A collector in western PA had one and was happy to part with it. When I offered to send her a brick in return or pay for postage she refused. She’s collected over 4,000 bricks since 1988, she told me, and at this point was more interested in making people happy than collecting more bricks.

Within a few days, she had pulled a McFeely from her collection, boxed it up, and sent it off through USPS to my door.

Another little piece of history in my collection. But this one is different. Yes, this brick connects to the history of brick-making and the American industry, but it also connects me to my fellow collectors around the country. Beyond that, it connects me to the spirit of why I do what I do – be it teaching, photographing, or researching. This is what I take from it:

Mr. Rogers asked us to be the best we can be and to see that potential in others. What can we do to make this world a better and more just place? Let us start by looking at how it is built. And let us also look to the example of Mr. Rogers by creating buildings, cities, and systems that help people. So that we might better our world – for everyone.

——————————-

I want to give thanks to two papers that were of invaluable help as I researched my bricks: “Tapestry Brick Dwellings: The Emergence of a Residential Type in Brooklyn” by Jonathan Taylor and “Early 20th Century ‘Face Brick’ as a National Industry” by Julie Rosen. I also want to recommend the wonderful book The Good Neighbor by Maxwell King.